Health

Designing with – not for – the Changing Face of Global Health

Sheryl Cababa

“How do we integrate human-centered design in problem solving for global health?”

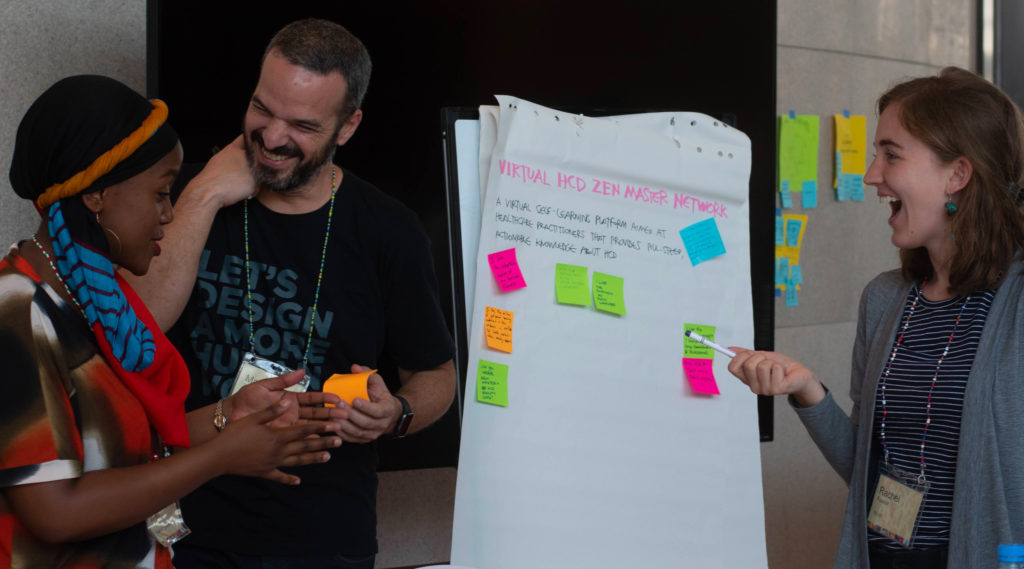

This was the question posed at the Gates Foundation and USAID human-centered design and global health convening: DesignforHealth: Nio Far Dakar. In Wolof, “nio far” means “we are together.” It was an appropriate title to the gathering, which brought together more than 70 invited design practitioners and global health experts from the world over for three days of reflection, ideation, and strategy.

As a host city, Dakar is the perfect venue for discussions about the future of human-centered design. The city is rapidly changing, from its loss of public spaces for children, to its role in Chinese investment in the region, to its importance in modern African art. The conference took place at the beautiful new Museum of Black Civilisations, which opened in January 2019. As a venue that is reflective of a changing Africa – and partially funded by the Chinese government – it is symbolic of how our global future is moving from north to south, and from west to east.

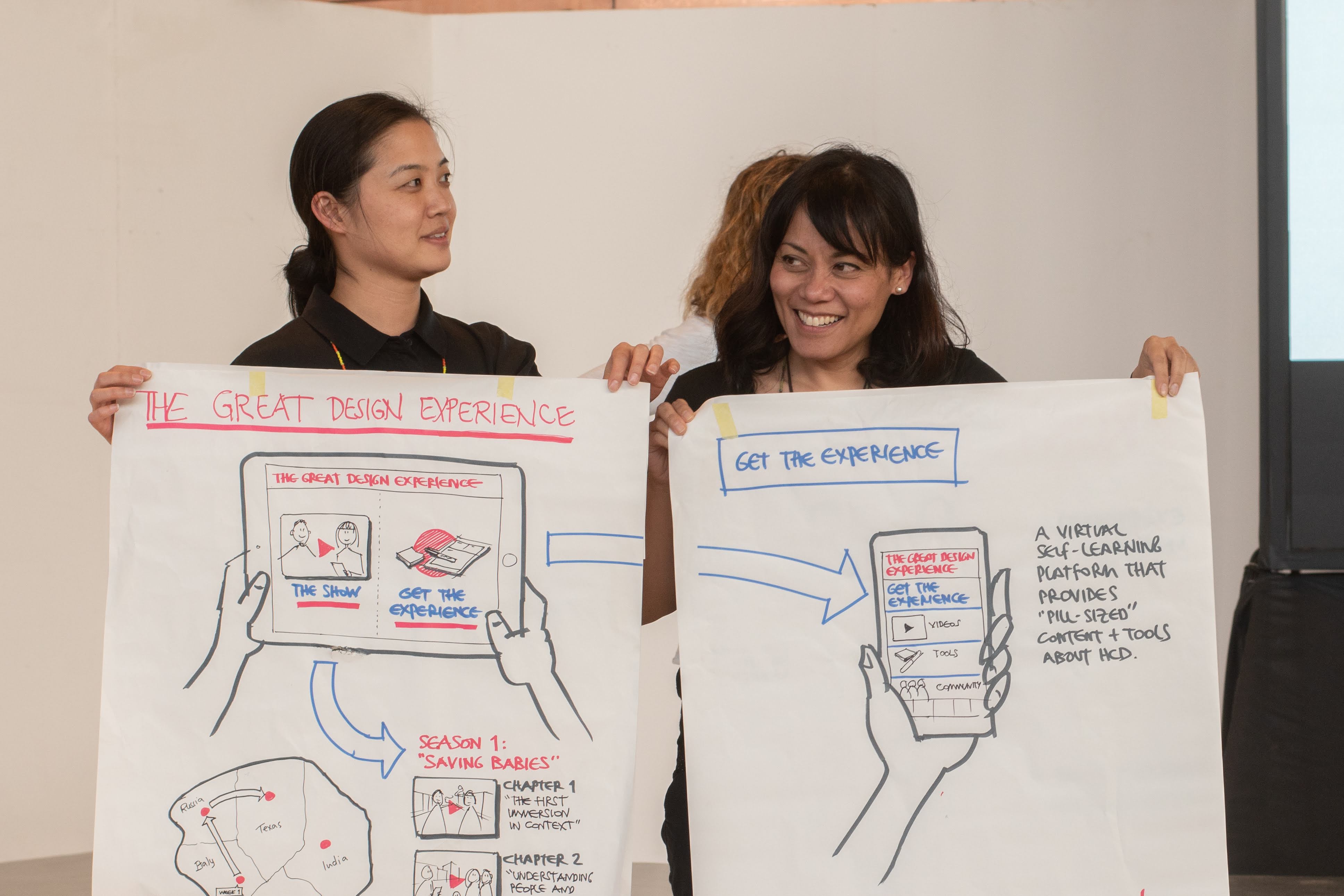

Over the course of the convening, we broke out into five “missions” to envision the future of human-centered design within global health: achieving scale, creating a design curriculum, managing design, understanding the return on design, and developing integrated approaches. Each mission had a mix of design practitioners and global health experts from organizations as diverse as PATH, McKinsey, Nairobi Design Institute, and the Clinton Health Access Initiative.

Working through these challenges with my peers in design and subject matter experts left me with three key takeaways on designing for global health.

1. Understanding global trends helps shape our thinking on the future of our design practice.

To kick off the workshop, Mari Tikkanen of social impact company Scope introduced trends to think about as we consider our mission of using human-centered design in global health. Urbanization, changing demographics, and transformative tech were key themes, all of which are affected by our changing climate. For example, I learned that there are currently about 19 megacities (a city with a population of 10 million or more). By 2030, there will be an additional eight megacities, all but one of which will be in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. In order to engage in human-centered design, we need to better understand cultures and ways of working in the global south as this is where we can have the greatest impact on global health. A Western lens on global problems is no longer enough.

2. User-centered design (UCD) is not equal to human-centered design (HCD).

Engaging with a group of talented human-centered design practitioners reminded me how often the tech industry uses the term “human-centered design” while actually practicing “user-centered design.” The difference matters. When we are solving for large-scale problems that touch many different stakeholders, the person who “uses” a design solution is just one stakeholder. Human-centered design should take the entire context into consideration, including those who may not be direct users. For example, with medical devices used in hospital settings, it may be hospital administration that has a greater influence on a device’s use than direct users. Examining the outcomes of our solutions on a broader set of stakeholders helps us develop programs or products that have fewer negative externalities and the most positive impact.

3. Want to be more inclusive? Engage in co-creation.

As we spoke about how to create a design curriculum, the conversation revolved around investing in design as part of in-country global health programs. It reminded me of an exhibit at the Gates Foundation Discovery Center called “Design With the 90 Percent” that explores designing for marginalized communities. “With” is the operative word here: what does it mean to design with those who are the beneficiaries of our design work, rather than designing for them? It means engaging in the hard work of helping non-designers contribute to our designed solutions. In designer Chris Elawa’s excellent article “Stop Designing For Africa,” D-Rev CEO Krista Donaldson says, “Without immersion with users, without being in-situ, without a sense of culture, language, norms, and deep understanding of the problems faced , an iterative product development process slips from market-pull to technology push.” In other words, we need to understand the human need first, and what that requires is help from the humans whose problems we are helping to solve. Some ideas for greater inclusion: investing in cultivating in-country design expertise and training on-the-ground community health care workers in design thinking skills and processes to help them innovate in their work.

As we see a convergence of technology, healthcare, and non-Western centers of power, we can use human-centered design to inform a shift in thinking. In order to be able to respond to the pace of global change, let’s ask ourselves, “How might we apply a creative approach to large-scale emerging health problems?” The world can’t afford to wait.

Read Next: