Mattia Vettorello (The Briefing.Today): Designers create the many products, services, and applications that we interact with in our daily lives. Each new addition to the system means that known and unknown consequences will follow.

Today, I’m joined by John Rousseau to explore responsible design and systems in flux. John is a partner at Artefact and leads teams in strategic foresight and speculative design. Thank you, John for being here with me today, and welcome to the show.

John

Rousseau: Thanks

so much, happy to be here.

MV: We currently live in a

situation where individual responsibility is key to the health of society at

large. How do you define responsible design?

JR: Artefact thinks about

responsible design in terms of a set of fairly big ideas that pertain to how

innovation should happen. There’s responsibility, say, at a societal level in

terms of just doing the right thing, broadly put. In terms of design

specifically, it begins with being inclusive of multiple stakeholders. Traditionally,

design was primarily concerned with the user, and I would say that it’s still

largely concerned with the user. But when you focus just on the user, you miss

a lot of other stakeholders in the system. You miss people who are impacted by

the things that you make, you miss the broader societal impact, and you miss

the planetary impact.

The

first aspect of responsibility is really just being stakeholder centric. Beyond

that, it’s thinking about all of the ways in which stakeholders are impacted

over time. So thinking about things in terms of complex systems and root

causes, how we might use design to shape preferable futures, and of course

being cognizant of the impact we make, both now and in that long-term future.

MV: What I’m hearing is that we

need to build in an extra layer when we design, looking not just to design for

a few months or years from now, but introduce a future layer. That’s where the

responsibility comes in. Understanding what the consequences could be.

In

practicing responsible design, is the designer responsible for what she or he

designs? Or is responsible design designing something that lets users be

responsible for their own actions?

JR: Traditionally, designers haven’t

had a lot of responsibility – or taken it – because they mostly work on behalf

of others who commissioned them to do something. The designer is merely a cog

between an organization or corporation that wants to accomplish something and

an end user of that thing.

What

needs to shift is both designers feeling like they actually do have some

responsibility for the outcomes they’re creating, but also recognizing that

that responsibility exists in an ecosystem of others. It exists in partnership

with those that are commissioning, responsible for funding, or benefiting from

the work, as well as those on the other end who are consuming and using it.

If

we took something like social media as a product, we could say “Nobody is

forcing anyone to use social media, so it’s a user problem.” We could also say,

“A lot of aspects of social media are designed to be addictive on purpose, so

that’s a designer problem.” Or we could say, “The business model of social

media is corrupt because it’s based on monetizing attention and that’s a

business model problem.” All of these things are different layers of the same

problem, which is to say that the design itself can’t be responsible unless all

of those components in the system are thought about in a responsible way.

MV: I really like when you say

all these aspects should be seen and designed through a responsible lens. Human-centered

design is itself limited by the human. It gives centricity to the human, when we

need to look at things from a complex, systemic perspective. What’s your

opinion on moving the focus from just human-centricity, which is quite static, to

enlarge it to a systems perspective? We can call it system-centric design or

ecological, bio-centric design.

JR: I really like that framing,

but I think that we’re probably a long way away from it. In large part because

of the fact that designers still exist in this intermediary space between

corporation/entity and user.

In

the future, moving toward a more ecosystem view of how design functions will be

required. That will by necessity mean that we have to reinvent the processes of

design, the concerns of design, and the business models of design. A lot has to

change in order to work that way and think that way. We would need to think of

design as a continuous activity that is continuously adapted to an external

environment. That means that we have to get better at looking forward in terms

of how we anticipate the external environment changing; it means that we need

to get better at anticipating unintended consequences, recognizing them when

they exist, and then adapting or pivoting; and it means that we need to get

better at adopting a more adaptive set of behaviors, in general.

If there’s

reason to be optimistic about that, it’s in part due to the fact that design

has become an internal competency within many organizations. In the old model,

where design was simply external, the corporation hired someone to design a thing

and the nature of the relationship created a condition where the design was

done and simply handed off and shipped. That mindset still exists even though

design is integral to many businesses and governments today. What can change

and needs to change is this sense of “done-ness.” Design needs to be engaged

consistently in a pattern of prototyping, measuring, evaluating, redoing,

envisioning, etc. It needs to be a more holistic and iterative process than it

is today.

MV: What you’re saying is that design should be really integrated at the C-level. Strategy should go hand in hand with design. In that way, design can be adaptable or at the least the product or solution can adapt to change.

JR: There’s been a trend in

design toward these kind of C-level roles like Chief Design Officer, and that’s

a positive trend except to the extent that those roles reinforce existing power

structures in hierarchies. If design remains the execution part of the

enterprise, design will continue to have the same sets of problems that we’ve

been talking about. The conception of design, in addition to the representation

of it, needs to change. Those two things probably happen in concert – one can’t

happen without the other. Design needs to become a more shared activity across

enterprises and organizations in order to evolve into a more agile, ecosystem-centric,

forward-looking set of activities.

MV: How can we democratize

design across and organization and across people, rather than just using it to

execute something? It’s more of a way of thinking, observing, coming up with ideas,

and connecting them. System-centric or ecology-centric design means complexity

and that’s not easy to talk or think about.

JR: I have a hunch that even

when we use terms like “design” we’re not talking about the same thing. A big,

broad term like that means a lot of different things to a lot of different

people, in the same way that “strategy” means very different things depending

on who you’re talking to.

I

don’t know if it’s necessarily true to say that design shouldn’t be about

execution or craft, because we still need to execute things and make things

aesthetically beautiful and functional – all of the traditional concerns of

design. Rather than asking, “does design need to be democratized?” perhaps

there needs to be a new discipline that exists in parallel. A discipline that’s

still design but perhaps more hybrid. It needs to borrow from economics and

strategy, it needs to have a lens on the business model as well as the

customer. It needs to have a lens on the future. It’s a different set of competencies

than aren’t readily represented at most organizations today. Design itself

needs to broaden its set of concern and perhaps some new adjacent discipline

should emerge.

MV: What should we call that discipline?

JR: There are people working on

that right now. There’s a program at Carnegie Mellon University right now

called Transition Design which is about large-scale systemic change. There is

the responsible design work that we are doing at Artefact, and lots of

different people have adopted that vernacular.

MV: At Artefact, designers are taking a broader, systemic look at challenges and implementing solutions to drive change and innovation. As you said, design speaks to people in different ways and strategy speaks to people in different ways. How do you encourage companies to take up responsible design and develop solutions to challenges within their industry?

JR: The most important thing is

to recognize is that it’s accessible. If I heard what I just said about needing

a new hybrid discipline that exists on a completely different mental model, it sounds

very intimidating.

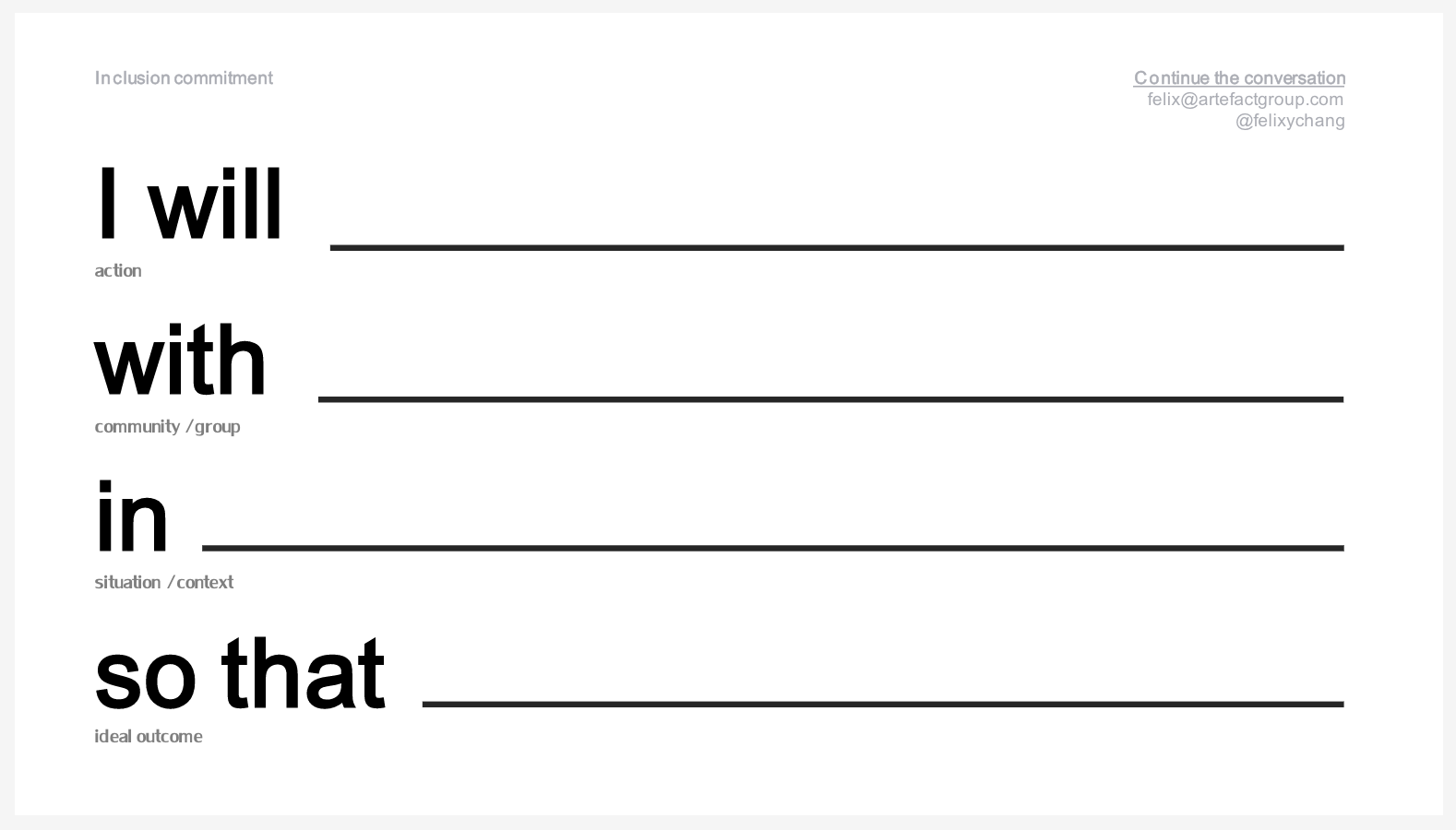

Responsible

design exists on a continuum, so even if you’re a designer who is primarily

working in execution – say designing products for market – there are all kinds of

ways you can bring a responsible perspective to what it is you do. It may be

just by shifting your mindset a bit and thinking beyond the user. Who are the

other stakeholders in the system? Have I thought about them? Have I thought

about the impact of the product I’m creating? Do I have any agency over those

impacts in terms of what I’m doing?

This

movement toward responsibility will have to happen both in a top-down and

bottom-up way. In the top-down way, it’s senior people recognizing the need to

make things more responsibly and changing entire processes and organizations in

line with those goals. For individual designers who may not have that same

degree of agency, there’s still a lot that one can do. I think the trick is to

find the small ways to move toward responsibility and actually seek it out, as

opposed to waiting for permission to bring it into your work. I see this

happening already in many different places.

MV: It’s always better to ask for

forgiveness than for permission.

JR: That’s a rule to live by in

design.

MV: Artefact also practices strategic

foresight. The COVID-19 situation has seen uncertainties increase exponentially

for everyone, from individual to organization. What is the connection between

design and strategic foresight and how do you implement that in your design

practice?

JR: Humans have always thought

about the future and the professionalization of strategic foresight has been

around for at least 50 to 70 years. In terms of its integration with design, Artefact

began to move toward it largely because we were looking for ways to be more

responsible and to think farther ahead. It was clear that there were a number

of instances where the tech industry had not done a good job of anticipating

future consequences, and the mental model was, “We’ll build it and see what

happens, things more or less work out.” It became clear to us that that was a

failed way to think about how the world works.

Strategic

foresight provides a pretty ready kit of tools that allow us to think

creatively about the future, create more useful images of the future, and use

those images in concert with the design practice to interrogate what it is that

we should make and perhaps what it is we shouldn’t. By integrating foresight

practices – whether it’s scenario-building or envisioning – into the design

practice, we’re in a position to become better designers because we adopt a

broader view of what is possible as well as a broader view of what should

happen. In this way, we can better integrate our values into the futures that

we are creating in ways that aren’t as readily accessible if we don’t think

long-term.

MV:

Sometimes

it’s hard for a company – or anyone – to envision what the future could look,

feel, and sound like. It’s very hard to put ourselves in the shoes of someone

in 2030 or 2050. How do you demonstrate the power and benefit of merging design

and foresight?

JR: The idea of designing for

the future has been around for quite a while. Thinking back over the last

decade of design consulting, a frequently recurring project type is “The future

of X.” The future of work, the future of mobility, etc.

The

traditional design firm would think ahead to what was technologically possible,

try to envision future needs, and essentially create speculative

representations of future products that were intended to inspire innovation

internally: north star products, services, and concept cards for the future. A

lot of this, while it was fun and interesting to do, was not always

particularly rigorous in terms of developing a sense of the tensions involved

in this future. Who are the stakeholders? What’s happening more broadly?

What

we’ve been trying to do is add rigor to this process. As our clients have

become more sophisticated in recognizing the existence and the value of

foresight, we have been starting to get requests to do these “Future of X”

projects in slightly different ways: to either take a broader lens, or

explicitly create scenarios, or otherwise integrate aspects of longer-term

futures thinking in a more rigorous way, with the innovation charter that we’re

also often tasked with. That’s what’s different about doing this at a design

firm as opposed to a foresight consultancy, because our job doesn’t really end

with, say, the image of the future. Our job ends when we have a strategy and

set of ideas that are meant to live within that future.

The

secret superpower of design is the ability to make something tangible and to

realize it in a way that isn’t just description. If I were to point to one

weakness in the traditional foresight process, it might be that it relies on

narrative and words, which are great, but not always sufficient. A lot of the speculative

design practice is critical and not necessarily directed toward creating a

better future. We are trying to take the best of all of those worlds and put

them together in a way that creates new kinds of value. How do we think more

creatively about the future in a structured, rigorous way? How do we blend that

with innovation programs in such a way that we can think more creatively and

orthogonally about what is possible and what we might make? And how do we turn

that into something tangible, that hopefully is more useful to the organization

because it’s grounded in a broader set of ideas than what we perhaps would have

done in the past?

MV: That’s fascinating. I like your proposition of merging the two disciplines, where we don’t just speak to the narrative, but we act on those words and give a physical form to it, rather than leaving companies with utopian and dystopian futures but nowhere to take those futures.

JR: Exactly. The way we think

of barriers or boundaries between disciplines today – the reason we have a

separate discipline called foresight and a separate discipline called design

and a bunch of sub-disciplines within that – is largely the result of the

industrial revolution and the effect on the economy of dividing up knowledge

and human labor into discrete categories. It’s worth noting that it hasn’t

always been that way.

Many

of the biggest breakthroughs in human history have come about as a result of

hybridity – people who are combining different streams of knowledge together in

novel ways. We shouldn’t be afraid of that. As designers, for example, we

shouldn’t be afraid of being amateur futurists, and futurists shouldn’t be

afraid of being an amateur designer. It’s really about looking more broadly at

what is possible and choosing the methods and assembling the right

collaborators that will achieve a novel result. There’s no reason to continue

doing things the way we’ve always done them simply because that’s the way we’ve

always done them.

MV: Exactly. We need

responsible design in order to adapt to changing circumstances and systems in

constant flux, but we need to adapt in an active way. By building stronger,

multidisciplinary teams, we can design more resilient, responsible, sustainable

solutions. Thank you so much, John.