PATH

How design can improve maternal health

Design

The power of prevention and intervention

PATH is an international nonprofit organization that transforms global health through innovation. PATH takes an entrepreneurial approach to developing and delivering high-impact, low-cost solutions, from lifesaving vaccines, drugs, diagnostics, and devices to collaborative programs with communities. Through its work in more than 70 countries, PATH and its partners empower people to achieve their full potential.

PATH and Artefact partnered together to investigate and explore solutions to one of the most serious yet preventable health challenges in the developing world: maternal morbidity and mortality. We set out to identify the factors that influence how and when new mothers seek care in these rural areas. Our goal was to design diagnostic product concepts that would reduce the life-threatening infections that occur during pregnancy and labor.

“One of the most successful experiences in our project on maternal and perinatal infections was the collaboration with Artefact for the primary research in-country. Their use of techniques such as storyboards for use scenarios and hypothetic product concepts provided us with richer, more complete data.”

Grounding care in a user-centered perspective

According to the World Health Organization, in 2010, 287,000 women died during pregnancy and after childbirth. The issue is most severe in remote rural areas of developing countries, where information access, cultural beliefs, and environmental conditions serve as barriers to receiving proper care. One of the main causes is untreated, yet often easily preventable: infections. During our partnership with PATH, we challenged stakeholders to rethink how pregnant women and the caregivers who influence them, could detect early signs of infections and subsequently seek treatment. Our approach was grounded in a user-centered perspective and began with ethnographic field research in Bangladesh and Uganda. We aimed to deeply understand the environments, social systems, and cultures that impact care-seeking behavior and ultimately, life-threatening infections.

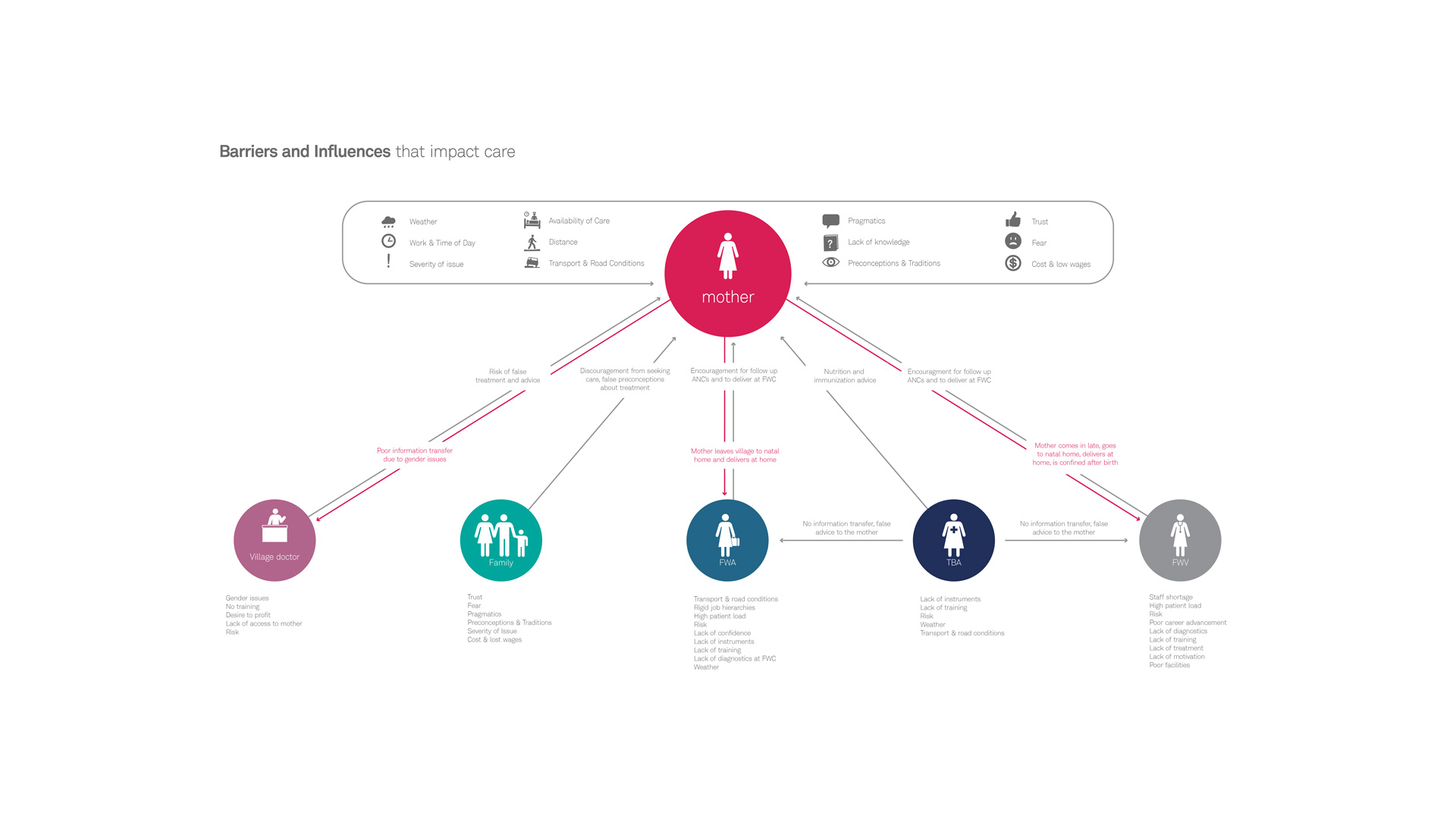

Recognizing formal and informal influences on care

At the outset, we recognized that women receive care and advice from a wide variety of places during pregnancy. Our goal was to identify these information sources and understand which are influential, which act as barriers, and which come from formal (i.e., trained) vs. informal (i.e., untrained) health care providers. One key discovery that impacted our product design criteria aligned around providing a strong sense of authority. Pregnant women’s primary points of care are family members, traditional birth attendants who are largely untrained, and formal care providers who have approximately 2 days to 1 week of training.

In addition to this, pregnant women are seldom “in-charge” of their own health-related decision-making. These insights meant it was imperative that the diagnostic device provided authoritative and unambiguous evidence to women, their care providers and family members to seek treatment (see infographic below). It is only with this type of information that those involved would be willing to reconsider deeply ingrained cultural beliefs or take on overcoming barriers, such as treacherous road conditions, to seek formal care.

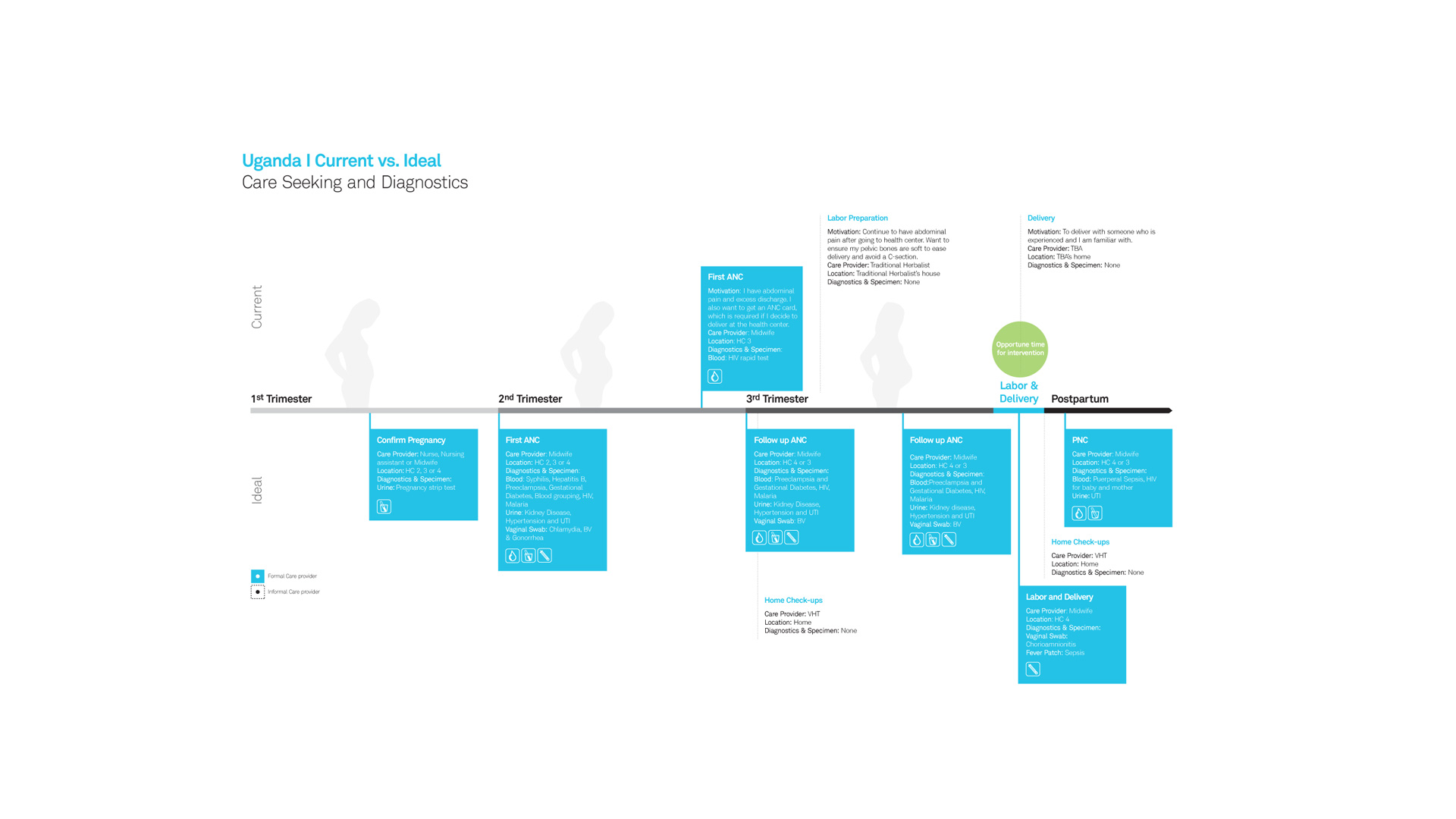

Finding the opportune time for intervention

No matter how perfectly designed the diagnostic tool was, we realized that if it wasn’t disseminated in a culturally acceptable way, widespread adoption would not follow. Through immersive research, we identified several factors that keep women from giving birth in clinics or hospitals, thus increasing the risk of infection for themselves or their babies. One of these cultural factors is the fear of “the evil eye” (a curse) that might be placed on a vulnerable newborn.

Fearing this, women deliver babies in their homes, or in the homes of traditional birth attendants. The often unsanitary conditions of childbirth and the low visibility in the environment, as well as the lack of training of caregivers, mean that labor can be extremely dangerous. We had to accept this strong bias towards giving birth at home and reframe this risky infection period in a way that would allow us to introduce the diagnostic tool, yet not threaten traditional beliefs.

Understanding acceptability within cultural context

We recognized that we could have the most impact by introducing the diagnostic during labor (see infographic above) and set out to ascertain the ideal form factor of the diagnostic. Collecting a specimen such as blood or urine might be most accurate, but would it be acceptable, and therefore, practiced? To learn about acceptability, we conducted scenario-based acceptability research with pregnant women, their mothers-in-law, husbands, and other people who influenced how they sought and received care.

We discovered that women were not comfortable self-administering diagnostics that require any type of specimen collection. They also did not trust birth attendants, family, and community members to collect specimens or to interpret test results. Not only did they worry about testing accuracy, but they were apprehensive of the possibility that gossip in the close-knit community would strip them of confidentiality.

From insights to solutions

After months of discovery-design-iteration cycles, we formulated product design criteria that would serve to inform the development of the infection diagnostic. Criteria included specifics about who should deliver the diagnostic and how it should be administered, given the location of use. For example, if formal providers have the opportunity to provide care, the diagnostic should provide on-the-spot diagnosis to help patients avoid additional trips and also be bundled with the frequently used “maama kits” women are familiar with. If the diagnostic is used at home with an informal provider, the diagnostic must provide authoritative evidence to seek further treatment, be administrable by patients themselves, and not be invasive.

We also explored several design concepts that met these design criteria. One concept is a fever patch that women would wear immediately after labor. The patch can detect a continuous fever over a 25-hour period, which is a signal of infection at such a vulnerable time. As women experience intermittent fevers during labor, the seriousness of a continuous fever is commonly ignored. The fever patch is a non-invasive measure that shows when the wearer has a fever by filling with a red pattern that spreads over the patch. It gives an authoritative, yet unambiguous signal to women and their untrained caregivers that immediate help should be sought.

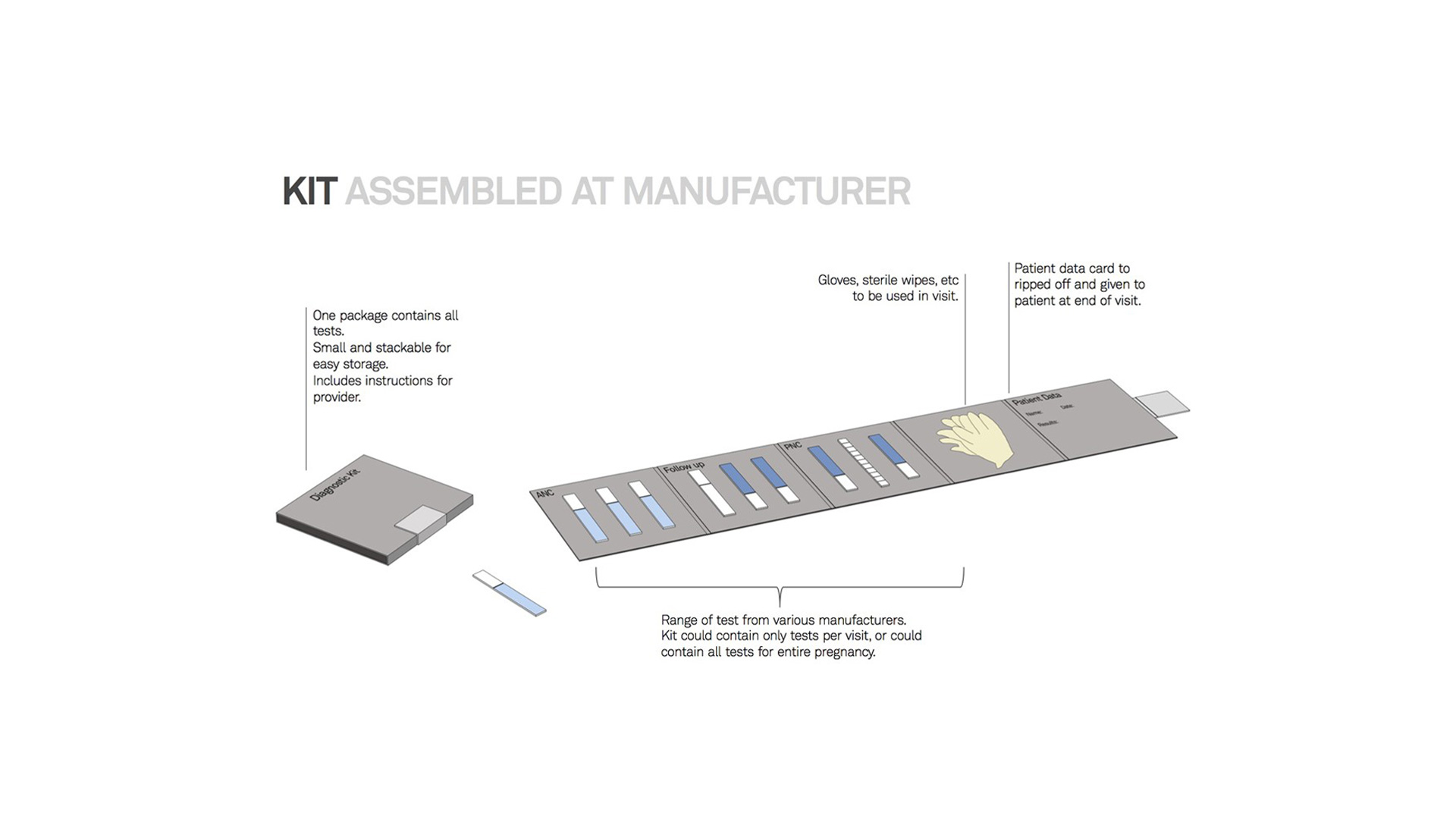

We also explored two kinds of kits, the first is a pregnancy care kit, assembled at the manufacturer, that includes diagnostics for all points of care: during the first antenatal care visit, the follow-up, and the post-natal care visit. The kit can be customized based on regional factors. For example, an HIV diagnostic would be included in Uganda, but not Bangladesh. The kit also could give providers guidance for how to administer diagnostics, and also, as patients could see which diagnostics they should be receiving, they could hold providers accountable to administer them.

The second kit is a diagnostic kit (pictured below) that would be assembled by a provider within a clinic. We found challenges in trying to keep current records, so the diagnostic kit helps keep patient information and test results together. The kit also incorporates the current method of test distribution and procurement that occurs in clinical settings, and can be customized based on what is in stock at the clinic.

Unraveling global health with human-centered design

Global health is an extremely complex area to improve upon because of several factors, namely the cultural nuances affecting daily decisions involved in seeking care. In order to improve upon these conditions despite the cultural barriers, it’s important that we apply a multi-disciplinary approach to identify opportunities for change. It’s crucial that the human perspective is at the center of these ideas. It was only by using this as our primary lens that we were able to uncover what stood in the way of care for mothers and provide solutions that are useful and accessible within the cultures where they exist. At Artefact, we are particularly passionate about this topic and could not be happier to partner with PATH on using human-centered design to tackle the complex global health issues of our world.

What we delivered

+ Generative research

+ Concept envisioning

+ Strategic assessment

+ Evaluative research

Next project

Chronicle